Nobel Prize-awarded CRISPR technology is subject to on-going patent litigation

23 November 2020

They will get the award on Dec 10, but who owns the patent rights? There is an intense patent battle evolving around the discovery of the gene-editing technology CRISPR.

The main protagonists are Emanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, this year’s Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, and Feng Zhang, a leading scientist at the Broad Institute, who worked simultaneously on a similar research. At the core of the conflict lies the question who can claim patent rights for the use of CRISPR technology to edit human genes. The patent dispute involves the University of California, together with the University of Vienna, as the employers of Jennifer Doudna and Emanuelle Charpentier respectively, in opposition to the Broad Institute.

Who owns the gold mine?

”What we can see already is that this was a groundbreaking discovery opening up a completely new field with many medical applications and potential uses for the treatment of genetic diseases. Both the economic interest at stake and the innovation activity in this field are very high, the technology has literally opened a new gold mine attracting diggers. The patent activity, i.e. the number of CRISPR-related patent applications filed across the globe, has reached high levels as well”, says Jörgen Linde, European Patent Attorney at Zacco in Stockholm and member of the Chemistry and Life Science team. “It shows how important it is to file a patent at an early stage. If their universities had not done so, Charpentier and Doudna might still have won the Nobel Prize, but would nevertheless lack ownership of the Intellectual Property rights, the parent patents, and thus not profit at all from the financial return on their research. The quality of the patent claims does matter too, obviously, in order to make sure you cover the entire scope of an invention and potential applications can’t round your basic patent.”

Geographical division of patent ownership

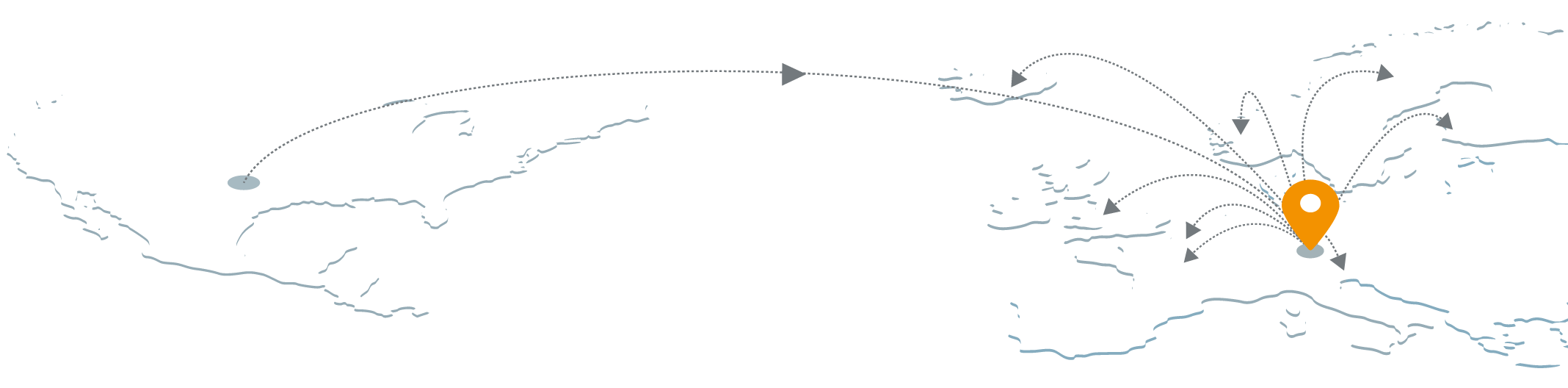

While heavily funded companies like e.g. Editas and CRISPR Therapeutics already have licensed or bought the IP rights from one party, the basic patent dispute is still unresolved. At this moment, one can see a geographical division where Charpentier/Doudna (or their filing universities) have gained an advantage in the European jurisdiction whilst the Broad Institute seems to be ahead of them in the US.

In Europe, the Broad Institute had to see its important parent patent EP 2 771 468 B1 revoked, strikingly enough due to a lack of entitlement (find the written decision here). As the number of named applicants differed and without the omitted applicant having transferred his rights, the priority claimed to derive from a US provisional application became invalid. The EPO Board of Appeal’s decision came at the beginning of 2020, but other patent families are still undergoing prosecution at the moment, with uncertain outcome.

In the US, the University of California, Berkeley et al. were indeed first to file a fundamental patent on CRISPR technology in 2012, but although Broad Institute filed its patent applications several months later, it got the basic CRISPR patent granted earlier due to the payment of a fast-track fee. However, a patent may be revoked by the PTAB if an opponent can prove its claims lack novelty and are obvious to a person skilled in the art in view of prior art. Why are Broad’s US patents still in place then? Mainly because they had narrowed the scope to editing mammalian genomes and provided specific data for eukaryotic cells in the application, while the University of California and its partners had grounded their earlier application on prokaryotes. So far, the University of California alongside with other opponents have failed to convince the Patent Trial and Appeal Board PTAB (USPTO) that the transfer to more complex cells was an obvious step to take for a skilled person, thus undermining the validity of Broad’s basic patent. The most recent ruling was issued in September 2020. It stated that Broad’s granted patents had priority for the use of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells, which probably is the most lucrative one as it includes human cells.

“The future patent landscape for CRISPR will likely be a mosaic of partially overlapping patent rights, where it is essential to have access to some patents that you have not filed yourself in order to put a product on the market” says Hampus Rystedt from Zacco’s Life Science team in Sweden. “We will likely see some consolidation of patents into patent pools or to a few major players. There will for sure be an interesting marketplace where small innovative companies can monetize their IP in this technology.”

Summary

Pioneering scientific research with huge potential in terms of both medical use and economic returns lies at the bottom of this unresolved patent battle with a geographical dimension. Anyhow, judging from the patent activity in the field, the unclear outcome has not prevented the development of CRISPR-related inventions and applications. “And maybe the patent protection period of 20 years will have expired before we even know who owned the fundamental patent rights”, as patent attorney Jörgen Linde comments.

If you would like to learn more about patenting the results of scientific research in different jurisdictions, patent litigation or licensing negotiations, please don’t hesitate to contact Zacco’s European Patent Attorneys Jörgen Linde and Hampus Rystedt or your closest Zacco office.

Back to all news